|

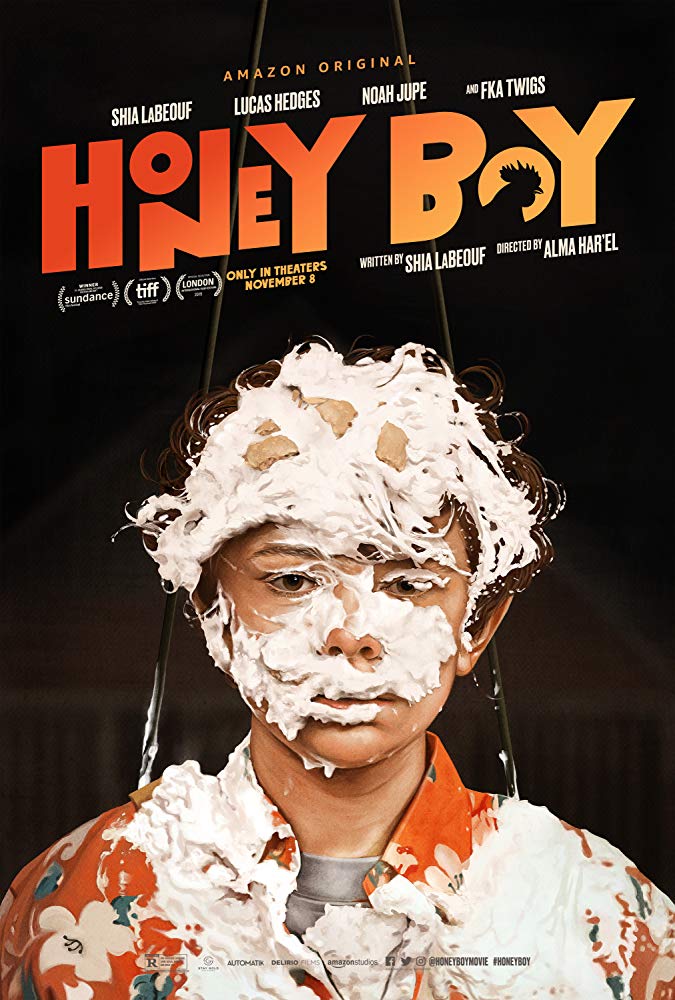

Honey Boy was directed by Alma Har’el from a script by Shia LaBeouf (yes, that one), and is based on LaBeouf’s own experiences growing up in the entertainment industry while dealing with his abusive, ex-rodeo clown father, who was a known felon. Noah Jupe and Lucas Hedges both play different versions of Otis (our main character) at various points in his life; the film begins with Hedges’ Otis being arrested for a DUI, put in jail, and sentenced to a rehab program in which he’s meant to work out his issues with the past, as Dr. Moreno (Laura San Giacomo) believes and informs Otis that he carries signs of severe trauma and PTSD. The story then shifts as Otis begins to recall his childhood, and the young actor (now played by Noah Jupe) attempts to grapple with the reality of living in a trailer park with his easily irritated father, who comes from a long line of alcoholics, and the power that his father had over his life, despite occasionally being employed by his own son. With the help of a young woman who lives across the street from him (FKA Twigs in her acting debut), his best friend in rehab (Byron Bowers), his childhood friend/mentor Tom (Clifton Collins Jr.), and Dr. Moreno, Otis begins to process the abuse he suffered for so long, learn to let go of his pain (which he thought was the only thing his father ever gave him that was of any value), and channel all of his mental and emotional baggage into a journal of dialogue which would go on to form the basis of the screenplay for this very film. This movie also stars Byron Bowers, Natasha Lyonne, Maika Monroe, and Mario Ponce.

Shia LaBeouf has been one of Hollywood’s most prolific actors since his childhood, truly shooting into stardom with his lead character in the Disney film Holes and starring role on the hit series Even Stevens, quickly becoming a sought-after star in the making, and most notably taking on the lead role of Sam Witwicky in director Michael Bay’s infamously terrible Transformers franchise for the series’ first three installments (though, to be fair, I do still somewhat enjoy the first one); he also later went on to land some supporting roles in films such as Lawless, Fury, and the indie hit American Honey. Most recently, he starred as Tyler alongside Zack Gottsagen and Dakota Johnson in this year’s highest-grossing indie film to date, The Peanut Butter Falcon (a movie which he’s really good in); yet none of these films listed have felt quite as intimate and personal for LaBeouf as this film does. LaBeouf has always been an immensely gifted performer, and anyone who’s seen even his bad movies can attest that he’s almost always on his game, but with Honey Boy, people may have to also contend that he is a force to be reckoned with in the writer’s room. Honey Boy may not be one of my absolute favorite or one of the absolute best films of the year thus far (to be honest, I did expect a little more from it than what I got), but it’s certainly one of the foremost examples of how Hollywood isn’t as out of original ideas as a lot of people like to say they are. The film pulses with a conflicted heart, one that desperately needs to be honest about what it wants to say, but refuses to condemn those within the frame that may be ultimately responsible for what’s being said, instead seeking to present them as they are without vilifying them (even if they are clearly villains); that is an insanely difficult line to walk, and it’s abundantly clear in the writing that LaBeouf is practically bleeding his own heart onto the page – the bravery of writing a movie like this (which LaBeouf wrote during his latest stint in rehab after being arrested for public intoxication while filming The Peanut Butter Falcon) cannot be understated. The film very much plays out much like an exercise in working through trauma, an exploration of the self, what might have ultimately influenced LaBeouf as a person, and a grappling with one’s ability or lack thereof to let go of and/or forgive the past and those within it. It’s a near herculean feat to get a script like this to work at all, much less to get it made with as much talent in front of the camera as behind it. Both Noah Jupe and Lucas Hedges do some of their absolute best work to date in this film, particularly Jupe, who can also be seen as legendary racecar driver Ken Miles’ son in James Mangold’s fantastic Ford v Ferrari (which is one of the best of the year). Jupe has to play a lot of different notes during each individual scene in being emotionally traumatized by Otis’ father yet also needing to find the courage to explain to him why he needs him in his life, and yet still being just too hesitant to say anything for fear of suffering further verbal, or even physical, abuse. Many of the lines Jupe has contain very adult-sounding dialogue, but where that wouldn’t necessarily work for another film as much, Jupe runs with it, and it makes sense coming from him, as he grows up largely around his father and on movie sets. But it’s not just Jupe’s line delivery that’s impressive here, it’s also his uncanny ability to understand every nuance of each line he’s saying, especially the more adult-sounding ones, without making it feel like he’s trying to genuinely be an adult in the film; Otis is a kid trying to talk to his father like an adult, but mostly failing because he is still just a kid, and Jupe’s performance is about as close to perfect as a child actor can get in this type of role. Hedges, too, gets a chance to really show off that he hasn’t gone anywhere since Lady Bird or Boy Erased, and in fact has a lot more to give as far as his performance range is concerned. The most impressive performance in this movie, though, and indeed the most impressive aspect (second only to the bold and impressive writing) is Shia LaBeouf as James Lort, a character based off of LaBeouf’s father, from whom he endured verbal and physical abuse. We see throughout the course of the film that LaBeouf is very protective of his son, often to the point where he needs to control who his son hangs out with or speaks to, which can lead towards that abusive behavior; he doesn’t quite understand what it’s like to be a kid in the entertainment business like Otis, but his blindness towards Otis needing a loving parental figure in his life rather than simply an encouraging one that pushes him to be better as a performer is what informs his character. Even as we the audience know how despicable Otis’ father is as a person, LaBeouf never lets the character fall into a place where he becomes an out-and-out villain, often giving the character a sense of insecurity which he projects onto his son, largely because his rodeo clown career never really took off. LaBeouf clearly doesn’t hate his father, but he also refuses to sanitize the trauma he endured as a child at his father’s hands, and his portrayal of James Lort is just nuanced and off-putting enough that occasionally, we let our guard down, as Otis does; this might be the best LaBeouf has ever been in this film, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see him walk away with an Oscar nomination for Original Screenplay or Supporting Actor. Honey Boy may not have impressed me as much as it impressed many others, but it certainly didn’t let me down either. The script by LaBeouf carries a raw honesty I haven’t seen from an auto-biographical story in a long time, the direction by Alma Har’el makes her a true force of nature to watch out for in the coming years, and every performance from Lucas Hedges to Noah Jupe to Shia LaBeouf himself leaps off the screen with near-perfect resonance. It’s original, it’s deeply felt, it’s occasionally brutally real, it’s raw, intimate, soul-bearing, and it’s one of the most uniquely told tales of this type to come along in quite some time. I’m giving “Honey Boy” an 8.2/10 - The Friendly Film Fan

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorFilm critic in my free time. Film enthusiast in my down time. Categories

All

|