|

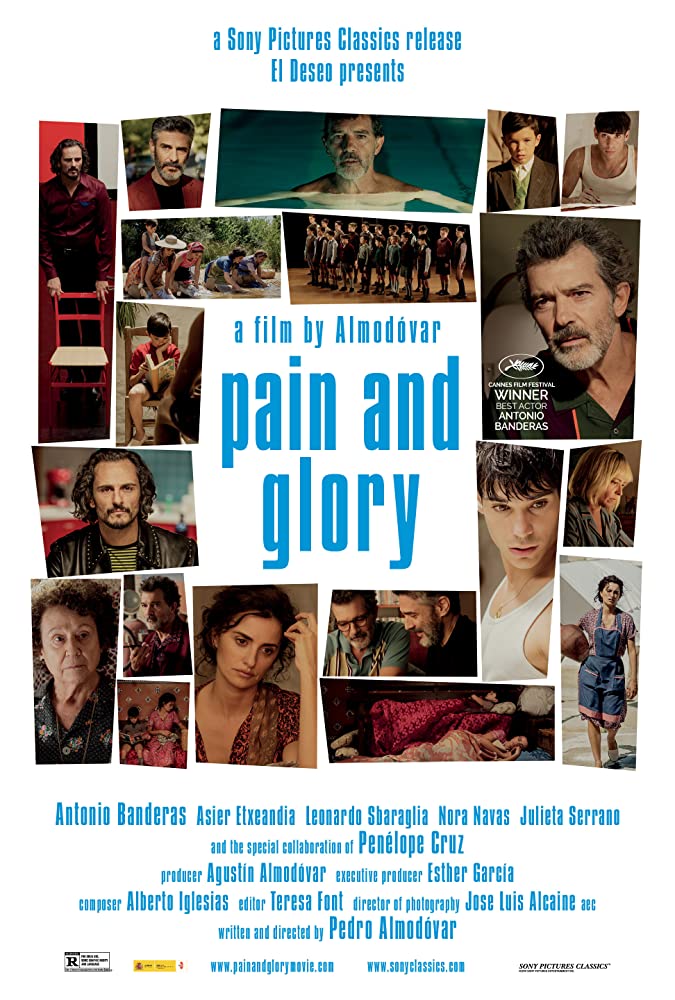

Pain and Glory is a Spanish film from writer and director Pedro Almodóvar, and stars Antonio Banderas as Salvador Mallo, an aging film director with his career and health in gradual but somewhat overbearing decline, who is consumed by a deep depression just as one of his early hits, a film called Sabor, is being prepped for re-release at a local theater with the original prints having been restored. After going to see the star of Sabor, an actor named Alberto Crespo (Asier Etxeandia) whom Salvador has not spoken to in almost 30 years, the two reconnect to reconcile their relationship and host the screening together. As the two discuss how their shared love of filmmaking and art, their absolute need to do it again but mutual inability to find a story they were particularly interested in telling, and how their lives have been shaped up to now, Mallo begins to reflect on the choices he’s made in his past, as well as those of his present, and begins to recall those moments in his childhood, living with his mother Jacinta (Penelope Cruz), when he first felt the pangs of desire, of need, of longing, seeking some answer within himself as to whether that is the place from whence his creative spark will re-ignite. The film also stars Leonardo Sbaraglia, Nora Navas, Julieta Serrano, César Vicente, Asier Flores, and Raúl Arévalo.

This film debuted all the way back in May at the legendary Cannes Film Festival, and with the buzz it got, it seemed to be the film to beat for the International Feature Oscar at the Academy Awards in 2020. Then Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (a masterpiece if ever there was one) ended up taking home the Palme D’or and did staggering numbers in limited release across the United States when it opened a few weeks ago, so most of the hype for Pain and Glory got a bit lost in the shuffle when it came to whether or not it even could enter the Best Picture race (which, for my money, Parasite could win if Neon plays their cards right). It didn’t walk away completely empty-handed, though, and one of the key wins it managed to snag was Best Lead Actor for Antonio Banderas. I’m not very familiar with the work of Pedro Almodóvar, and in fact, this is the first of his films I’ve seen, so I don’t really have a threshold for how well this stacks up against his other work; what I do have a (passing) familiarity with is at least some of the work of Spanish actor Antonia Banderas – not much that matters in proximity to his recent work, but enough that I know who he is and have enjoyed a few things he’s been in – so I was very much looking forward to seeing this film at some point, and delighted when I discovered it would be playing at the Kentucky Theater, and I could see for myself what that Best Actor Cannes win meant to that audience. Apparently, it means quite a lot. Let’s focus on Antonio Banderas first, since he’s the thing about this film most people would be familiar with, and because I just really want to talk about him in this movie. This is one of Banderas’ best performances in years, not the least of which is because it’s also one of the best-written characters he’s been able to play in years. As mentioned before, I only have a passing knowledge of his previous work, but even compared to the work I haven’t seen of his, I’d be willing to bet that this might well be his greatest performance yet; he’s exceptionally good here, and the way that he invites the audience to feel with him and reflect as he does without forcing the camera or the audience watching it to understand him is a nice, subtle reminder of just how good he can be when he’s paired with a great script and director (one with whom he apparently works quite often, like the Scorsese to his DiCaprio). His gentle ponderings are quiet and unassuming, but create a nonetheless affecting muse, a canvas on which Almodóvar is able to paint a careful portrait of ache and creative world-weariness. This really is more of a Banderas showcase in performance than it is a full-out story, but the story itself lends to that performance by making the whole point of the film the reflection and struggle to create; it’s essentially a “writer’s block” movie about movie-making, and what it means to genuinely pour your soul into what you create, as well as what happens when you refuse to create unless you can bare your soul by doing so. I’m not sure if the Academy will be any kinder to this film apart from Banderas in giving it any more than a base level of acknowledgement with a Best International Feature nomination, but I do know that Banderas, if he ever wasn’t before, is now in range to almost definitely land a Best Actor nod at the Oscars; that Cannes win was no fluke. Banderas’ turn as Mallo isn’t the only great performance in the film, either. Penelope Cruz has been getting back into great work lately with FX’s American Crime Story saga, The Assassination of Gianni Versace, and though her role is clearly as a supporting player here, she manages to stick in the mind almost as effectively and often as Banderas does. It’s not exactly a showy role, and probably won’t land her an Oscar nomination in this crowded of a field (especially for that category), but as Mallo reflects upon life with his mother in their little cave house with the white walls, one can very easily see how much his mother meant to him as a child, how heavily she affected his life, largely thanks to the correctly understated performance of Cruz. All the other supporting players are great as well, but in terms of performance, it her that stands out the most in that respect. It’s a shame the film might not do any better than International Feature as far as nominations go, though, because the movie itself is genuinely great, with a fantastic script that’s just as insightful as it is funny, heartwarming, heartbreaking, and wonderfully subversive. Almost nothing in this movie goes exactly where you think it will go, but it’s not as if the film is just subverting expectations; it’s playing with expectations most people wouldn’t have thought to have, and the fact that such a simple, quiet story could surprise me this late in 2019, even in ways I hadn’t given a passing thought to, is an unexpected joy to think about. Almodóvar’s direction, too, is excellent, and it’s clear that this is a story he deeply cares about telling, one he needs to tell, just as Banderas’ character needs to tell a story in order to tell it at all. The ending to this film is one of the most quietly subversive and meta endings of any movie this year, and seeing a director be able to pull off an ending like that without it being some mega-twist is a nice change of pace from the usual “meta” packaging a lot of movies seem to think they have to come in nowadays. Even if not all the seconds ring perfectly, all of them ring true, and it’s Almodóvar’s direction that allows them to seep into the frame without crowding it. If the film has any flaws at all, I only noticed one, but unfortunately, it’s one that I’m sure was probably the right choice to make for the film proper even though it still stuck in my mind after walking out of the theater; I won’t spoil the who, what, when, where (you get the picture), etc, but after reflecting on the film, I realized that one of the major players early on sort of just disappears from the movie about halfway through – not “reappears later,” just straight-up is not in the movie anymore afterwards. Perhaps it wouldn’t have served the story, and that’s why it was cut from the finished product, but it can’t help but feel like a fairly obvious inconsistency in an otherwise pretty great film. In the end, Pain and Glory wasn’t quite as magnificent as I had thought it would be, as impactful or emotional as I had hoped it would be, or as mind-blowing a masterpiece as its nearest competitor for International Feature, Parasite, clearly is, but there’s hardly any harm in being the second-best foreign film of the year when first place is also competing for best movie of the year, full-stop. At the very least, even a halfway decent effort on part of the filmmakers and performers would have gotten me interested in Pedro Almodóvar’s other work, but it just so happens that the writer/director has crafted a beautifully intimate portrait of what it means to desire and create, with a script that carries the necessary thematic power to drastically boost the performance of both his lead actor and his own direction of the film. I’m not sure how much longer it will be in theaters (especially for places that don’t play many foreign films), but if you can find it at a theater near you, definitely give it a shot. Your movie-watching history will be better for it. I’m giving “Pain and Glory (Dolor y Gloria)” an 8.9/10 - The Friendly Film Fan

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorFilm critic in my free time. Film enthusiast in my down time. Categories

All

|