|

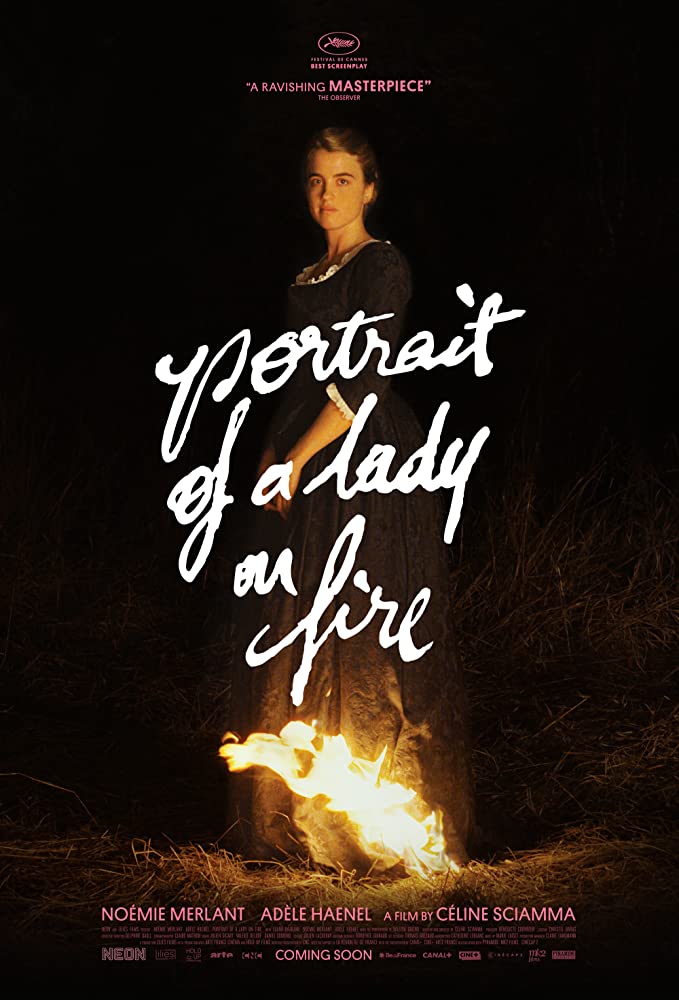

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is the fourth film from French writer/director Céline Sciamma, and stars Noémie Merlant as Marianne, a painter in late 18th century France en route to a remote island in the French province of Brittany, where she is to paint a wedding portrait of a young woman named Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), who is promised to a Milanese suitor. The request comes at the behest of Héloïse’s mother (Valeria Golino), who orchestrated the match after her other daughter, who was originally promised to the suitor, died tragically from suicide. But there is a tenuous catch to Marianne’s new project; Héloïse refuses to be painted. Believing Marianne to be a companion for walks, Héloïse reluctantly agrees to the company, and Marianne must learn to paint her through careful study when the gaze of her piercing blue eyes is averted from Marianne’s studious observation. As the two women come to know one another over the course of several days, forming a bond with the family maid, Sophie (Luàna Bajrami), in the process, they come to discover things about each other that neither of them expected to learn, and as their connection grows stronger, so too does their mutual understanding of womanhood, place, purpose, art, and what it means to love.

Before this film, I was unfamiliar with Céline Sciamma’s work, having never seen one of her films, though I had certainly heard of them before. In fact, her second and third films (Tomboy and Girlhood, respectively) made the critical rounds on many end-of-year Top 10 lists the years they were released, though her first feature film, Water Lilies, seems to have had less of an impact on the overall cinematic consciousness of most (although it did screen at Cannes). It should have been easy for me to know what sort of film I was getting into, and yet, as I sat down to watch Portrait of a Lady on Fire, I was entirely unaware of Sciamma’s name and the praise with which she had previously been showered, and would not connect my knowledge of her previous films to this one until performing preliminary research for this review and reading of her name and work under the list of director credits. All I had to go on was some strong word-of-mouth from critics that had already seen this film, as well as its reputation during awards season overseas. I need not have been excited, nor wary, however, for I did not know what would truly be in store for me on the other side of the closing credits; what this film offered me to feel was something entirely alien, yet wholly familiar, something so uniquely its own that there doesn’t seem to be a way to describe its nature (that being the nature of the film), nor its quality that would not in effect do disservice to its quiet power. The essence of something like this, of art like this, is such that I cannot find the language in any form – French, English, or otherwise – (nor do I believe I wish to), to relate to you even the idea of the of the sublimity to which I bore witness. Portrait of a Lady on Fire is as close to a perfect film as I’ve seen this year, and perhaps that I’ve ever seen at all. It is virtually flawless, entirely exquisite, masterfully written, and beautifully performed. It is the kind of film that comes out of a director not in full command of but in perfect harmony with their craft once in twenty lifetimes, every frame dripping with the patience, the care, the compassion of a woman painting her own portrait, inviting but not demanding that its soul drip onto the canvas of images it has to offer. It is entirely its own, but also 100% yours the second you lay your eyes on its beauty, allowing you to see it in all its glory, but also embracing your investment in its story, its characters, the movements of both them and the camera, declaring itself something for you and only for you, like a lover ready to finally arrive home to your arms. Its writing, each piece of dialogue and all the spaces in between, is balanced on a tightrope, so taut one can almost touch Sciamma herself as she glides across its center, no foot missing its mark, her eyes entirely on her destination, but aware of all that surrounds her. I could wax poetic about the wonder of this film for twenty of my own lifetimes, but I sense I must get on with the specifics of what works about it (there’s nothing that doesn’t, in case you were wondering). As mentioned before, the cinematography is exquisite. Not a single frame captured or produced by director of photography Claire Mathon feels out of place, and neither do any of the movements of those frames (the ones that do move, anyway). Each and every image is a remarkable portrait all its own, so much so that the halfway point of the film came up, and I hadn’t even realized that I had had my jaw on the floor nearly the entire time due to how breathtaking the movie looked the entire time. All of it feels so honest, so deliberately crafted and painstakingly careful that no one can look upon it and not have at least some semblance of the same reaction. But the camera isn’t the only thing building this film’s aesthetic power to a fever pitch; Dorothée Guiraud, too, as the film’s costume designer, make event the simplest of dresses, the most basic of clothing, carry meaning and weight not experience by the human eye since Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread, and even that movie had a lot more to work with in terms of pure choice. What Guiraud is able to do with just one green dress is nothing short of miraculous, and although France is not submitting this film at the Academy Awards this season, all critics bodies and awards pundits would be remiss not to mention her as one who should be a top contender for the prize in a world with any sense of cinematic justice. The performances, also (as mentioned before), are perfect. There is not a single one with which I can find fault and there is not a single moment in any of them in which I can probe for weakness. Both supporting characters, the maid Sophie and the Countess (Héloïse’s mother), are played to perfection by Luàna Bajrami and Valeria Golino, the former having much more screen-time, but the latter having no less power, practically commanding the screen when she gets to be on it. And yet, even as perfect of performances as those are, it’s the two main stars of the film that elevate it beyond mere perfection, and into the realms of heavenly wonder, with on-screen turns that can only be described as miracles of cinema. An oft-overused term to describe performances as magnificent as these is to describe them as “lived-in” but there is no description more apt for the work Noémie Merlant and Adèle Haenel are putting forth into their characters. This movie should be shown in acting classes across the globe as a masterclass in inner thought and body movement. Every eye twitch, every breath, every hand gesture by both these performers matters more in a single frame than most others do across entire films, and Merlant in particular is as startling a showcase in performance of any kind as anyone has ever witnessed. (Haenel matches her almost beat for beat in terms of pure quality, but we spend slightly more time with Merlant, so she has the advantage on that front.) Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a film of rare poise, its quiet power seeping into one’s soul, manifesting there in the same manner a lover’s kiss, placed just so upon the lips, moves subtly into one’s veins so that you would never dare to shake its warmth from your heart. In telling a story so simple, its complexities are laid bare by passion, Céline Sciamma has crafted the embodiment in film of the art which she seeks to elevate. This film is a subtly crafted, exquisitely executed marvel, a miracle of such magnificence, I will be remembering the first time I ever watched it a decade from now and further on; it is as close to a masterpiece as any, the most wonderful investment of one’s time and attention, and those who wish to know what perfection in cinema feels like will be invited, and encouraged, to turn to this eighth wonder of the world for eons to come. I’m giving “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” a 10/10 - The Friendly Film Fan

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorFilm critic in my free time. Film enthusiast in my down time. Categories

All

|