|

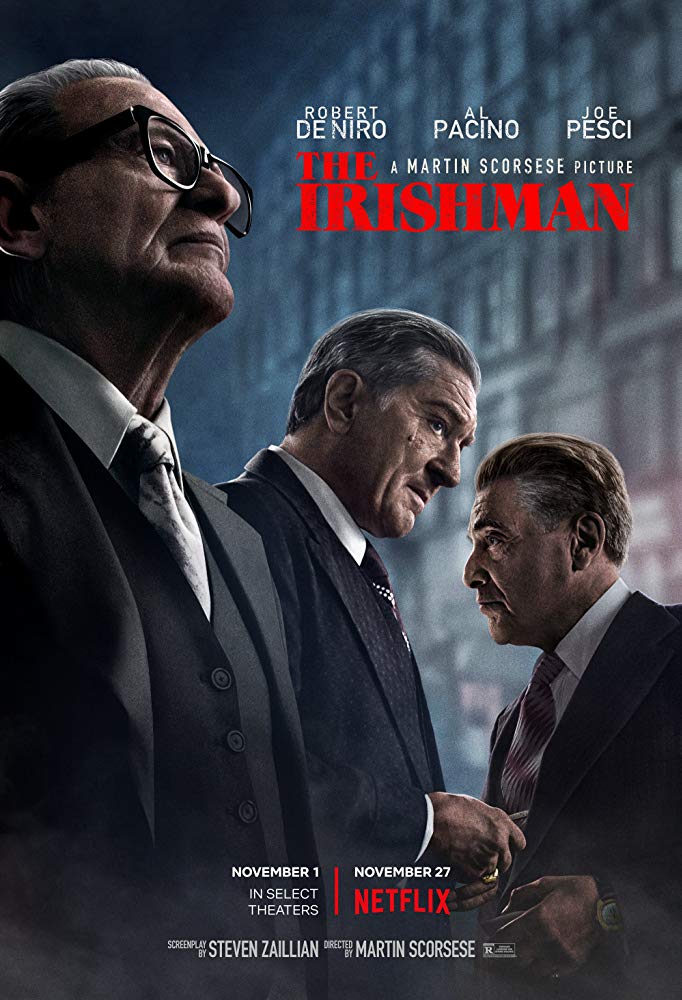

The Irishman was directed by Martin Scorsese from a screenplay by Steven Zaillian, and is based on the book “I Heard You Paint Houses” by Charles Brandt. It stars Robert De Niro as Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran, a regular working delivery man who happens to make the acquaintance of one Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci) after his truck breaks down near a Texaco station. When a botched delivery later on down the line leads to Sheeran seeking out a lawyer (as he’s been accused of stealing), he soon meets Bill Bufalino (Ray Romano), the family attorney and Russell’s cousin. Eventually coming back into contact with Russell due to he and Bill’s partnership, Sheeran is set to the task of becoming a mob hitman, under the direction of both Russell and union organizer Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino), both of whom Frank becomes very endeared to and close friends with over the course of his life and career. As Frank sits in a hospital dining hall recalling his past, working in, for, and with the mob, he reflects on the choices he made throughout his life, for better or worse, as well as his possible involvement with the abduction and subsequent murder of Hoffa, and the role he had to play in shaping the events of history. The film also stars Stephen Graham, Anna Paquin, Jesse Plemons, Bobby Cannavale, and Harvey Keitel.

Well, the wait is finally over. Upon hearing for nearly four years ago that The Irishman, a mob movie starring the big three titans of gangster performance and directed by the titan of gangster filmmaking, would be getting made, it immediately became one of my most anticipated films for whatever year it was planned to be released. This was a project anyone should have wanted to pick up, a surefire hit with more than enough potential for major Oscar nominations before the ink was even dry. After a while, though, trouble started brewing in the studio system and every major player that Scorsese pitched the movie to passed on it, perhaps believing that no one would want to sit through a 3+ hour movie (boy were they wrong), or that even if they did, this wasn’t the kind of film that would make the necessary amount of money in the box office to justify the technological expenditures the project would require. Enter Netflix, the behemoth streaming service that greenlights just about everything and throws money at projects like it’s worth more than Jeff Bezos (though, apart from a money standpoint, it pretty much is). Netflix has been attempting to crack the Oscar curse against streaming services for years now, and with the huge splash made by last year’s Roma (my #1 movie of 2018), the timing could not have been better for the service to throw a large wad of cash ($160 million) in Scorsese’s direction. Those investors must be pretty happy too, because that investment paid off in spades, resulting in one of Martin Scorsese’s most accomplished films since Goodfellas and easily the best he’s done since The Departed. The Irishman is a fantastic movie, although it may not be the movie that the initial marketing promised to deliver. This is far more in the vein of the more emotionally charged final trailer: a ponderous, reflective tale of friendship, betrayal, loyalty, negligence, old age, guilt or lack thereof, and violence so unflinchingly plain, it seems as if Scorsese is actively trying to tear down the gangster life which earlier in his career had seemed such a fun thing for him to explore, such as in Goodfellas. It’s not really proper, in that sense, to call this a mob movie. In fact, it’s probably better described as an anti-mob movie, a post-gangster epic that strips the profession of any grandeur or glamor and presents it as it would more than likely be, resulting in what might be the most genuine tragedy in Scorsese’s storied genre history. The violence is sparse but brutally un-stylized when it occurs, making it all the more jarring even though it doesn’t happen quite as often as one might think it would. There’s a lot of downtime between the jobs to which Frank is assigned, and it gives him a lot of time to think about what it is he’s being asked to do; as such, we get to see him have a lot of conversations about developments that might come, but never do, and the realism of his time working for mob being slow, drawn-out, and mostly filled with a lot of car rides gives Scorsese a new perspective with which to approach a story like this. Frank is not a charismatic character, but it’s because he’s just a simple working man that the tragedy of his time in the mob is so profound. It may not hit you until the last 30 or 45 minutes, but one soon realizes after the main portion of the plot is over that the whole point of the film is that living this kind of life separates oneself from what living really is. Being with people who love you, who you love, being close to one’s family, paying attention to what matters most – these are all things Frank inadvertently gives up in the name of “protecting” them as he works for the mob. His bodyguard approach to the things that matter in life means he always has his back to what’s important because he’s so concerned with what could take it away, both for himself and others he cares about around him. The performances are, as expected, some of the absolute best of the year, and you can count on pretty much all of the leading three men in the film entering their respective acting races with Oscar nominations come January. These three, whenever they’re on screen two or three at a time, have some of the most natural chemistry in any mob film, so much so you could swear they’d been doing this their entire lives. All of them pull off some of their best work here, not the least of whom is Robert De Niro, who gets to play a character much less secure in his choices than we’ve typically seen him. Frank comes off as the most regular guy out of all three, and it’s this regularity, this grounded-ness, that give De Niro the ability to pull off the performance that he does in this film. Pacino, too, working with Scorsese for the first time ever, delivers one of his best performances as Jimmy Hoffa, and we understand throughout the picture why he becomes so endeared to Frank as Frank becomes to him. There are time when he gets to be more over-the-top, the thing Pacino is so good at selling, but those time when he’s more subdued are just as powerful and natural. Pacino does fantastic work here alongside De Niro, and it’s a safe bet that after this, he may work with Scorsese a lot more. The cream of the crop, though, undoubtedly, is Joe Pesci as Russell Bufalino. Leave it to Pesci to come out of retirement just to work with Scorsese and deliver his best performance in decades right out of the gate. Pacino has the showier role in terms of what he gets to do, but Pesci’s quiet, subdued Russell is an almost perfect inverse of the kinds of roles this guy has typically been given. He’s so good at the composed, even-tempered mob boss type that you’d swear the guy in Goodfellas isn’t even the same person, and the simplicity of his performance, his demeanor and cantor, are so controlled it honestly might be his most impressively confident stretch of acting to date. And yes, I’m including the “funny how?” scene. There were two main things people were concerned about with The Irishman, the first of which studios noted but didn’t seem that concerned about, and that is the de-aging effects on Robert De Niro throughout the film. Netflix is a big company, but even they don’t have the pockets that Disney does, so pulling off de-aging is probably where most of the budget for this film went, and to be honest, it matters so little to the story at hand, I didn’t even notice when it was used apart from one scene set very early in Frank’s life. Besides that, the effects are pretty much seamless, entirely fluid and brilliantly invisible to the point where when you walk out of the film, it might not hit you just how incredibly well the VFX team managed to pull it off until much later in one’s post-movie ruminations. This story spans decades, and the sheer amount of visual effects required to tell it for just one character, let alone as many as are in this film, is a staggering achievement for both Netflix and this VFX team. The second thing concerning people was the length; one of the reasons studios likely passed on the film is due to its mammoth runtime at three and a half hours with no intermission. As far as that’s concerned, the film does run a bit on the long side, and you do feel it sometimes, but it’s not really something that comes to be much of a bother at all when all is said and done. Mob life is sometimes pretty slow, so it makes sense that there are large stretches of the film that take place between action where the script is essentially just conversations between two or more people about what the next bit of violence or lack thereof might entail. This leaves one with the understanding that while the film could speed things along a little quicker, there really is no narrative or thematic reason why that would need to happen, so you just accept that however long it takes to tell the story is however long it takes. This length also forces the audience to ponder whether or not the life they once enjoyed watching in Goodfellas is really as cool and fun as that film made it seem, basically pointing a finger at the audience and saying “hey, buddy, this life is not what you think it is, so stop glamorizing it and start reflecting on what it would actually mean to be part of something like this.” Despite this being one of Scorsese’s best in at least a decade, though, there are one or two things that could have been improved upon. The film sets up this lost connection between Frank and his daughter Peggy, played by Anna Paquin, but apart from a few shot/reverse-shots of the two sitting together at the breakfast table, we never really see their relationship develop in any meaningful way. The moments when she refuses to talk to or spend time with him do still have an effect, but due to Peggy’s lack of build-up as a character, they don’t have as much of an impact as they otherwise might have. It makes sense that the script would choose to have Frank’s wish to spend more time with her be made in hindsight, thus creating a greater tragedy to cause the rift between the two, but it still felt as though Paquin’s character could have been improved upon a bit. It’s part of the point of the movie that we really don’t spend any meaningful time with Franks family before it’s too late for him to do so, but it still feels as if a piece of the puzzle is missing somewhere, likely lost in the adaptation from page to screen. Also (although this is just a personal thing), I wish we had gotten just a little more Harvey Keitel. Still, even though one or two extremely minor things I had hoped to see more from (and can easily forgive in hindsight) weren't necessarily handled quite as well as the rest of it, Martin Scorsese’s latest directorial effort is sure to remind everyone why he’s one of the most revered filmmakers ever to do the job in the first place, a masterclass in storytelling that takes the mob movie and flips it on its head, presenting the hitman life in its truest, most raw form. A post-mob tragedy that deglamorizes the gangster life, The Irishman proves beyond doubt that the director of Casino and Mean Streets still has a lot of profundity left in him to pour into his work. The performances are all fantastic, especially those of De Niro and Pesci, and the melancholic themes of life eventually catching up to oneself as we look past what’s important in order to accomplish what seems urgent at the time make this movie one of Scorsese’s best, most insightful works, as well as one of the best films of the year. I’m giving “The Irishman” a 9.6/10 - The Friendly Film Fan

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorFilm critic in my free time. Film enthusiast in my down time. Categories

All

|