|

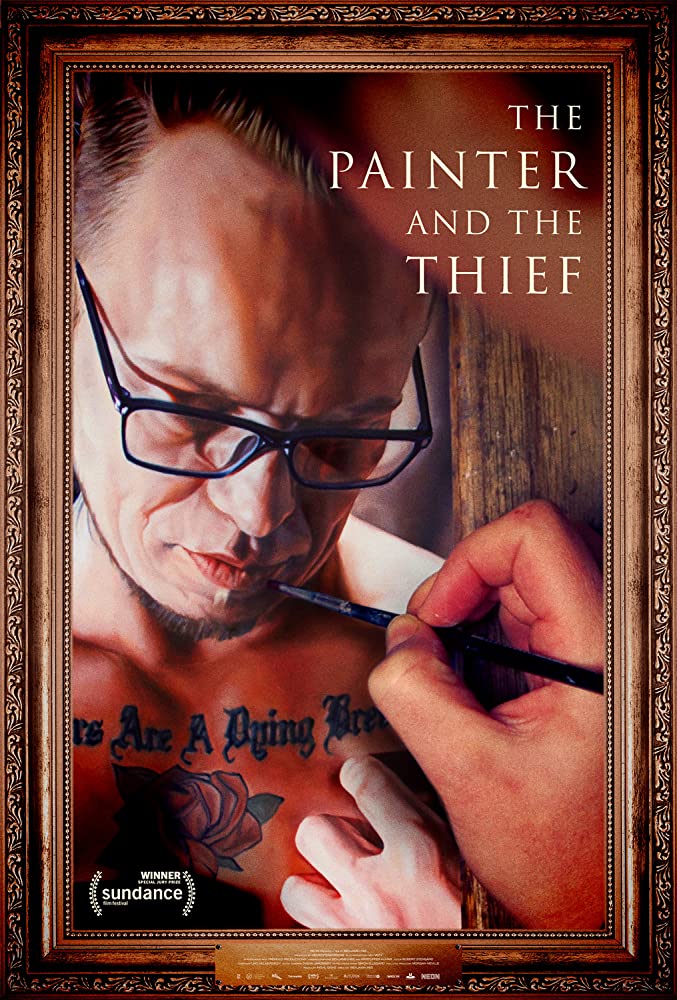

The Painter and the Thief is a Norwegian documentary feature from Neon Studios and director Benjamin Lee. It follows the complicated and strangely developed friendship between renowned artist Barbora Kysilkova and the troubled art thief/addict Karl Bertil-Nordland, whom she had met after Bertil-Nordland and an associate of his stole two of her most valuable large-format paintings from an Oslo exhibition in April of 2015. After tracking down Bertil, thanks to some security footage captured during the heist, Barbora speaks directly to him during a court hearing, and unbelievably invites him to her studio space in order to sit for a portrait, declaring that she will use him as her model for free. Taking no issue with this, as he regrets stealing her paintings, and is unaware of what’s become of them or the other thief with whom he pulled off the heist, Bertil agrees, and soon the two become inseparable from each other, intertwined in each other’s lives through shared stories of both their traumatic pasts and their mutual affinity for the power of art. As the film captures their evolving relationship to each other, many things come to light that neither of them ever expected to have to reckon with, and each must reconcile themselves with the darker corners of their own lives, as well as decide whether this friendship is worth the risks they each take every day to make it work. This film was produced by Morgan Neville and edited by Robert Stengård.

Documentaries can be tricky when it comes to building narrative and exploring thematic concepts, largely because most documentaries are designed with a message in mind, but often no exact roadmap to getting wherever that message is meant to take the viewer. These types of documentary films often find that map along the way, using the means at their disposal to steer the films where they ultimately end up. Neon’s other hit documentary this year, Spaceship Earth (review here), has a story it is telling, but it is not a discovered story, or one that was dug up along the way in filming. Oftentimes, however, the great documentaries of our era, much like American Factory, or Icarus, are born of an accidental run-ins with much larger stories than the filmmakers originally intended to capture. These are the documentaries that stick in the mind, and none have more stuck in my mind lately than Benjamin Lee’s The Painter and the Thief, which tackles such subjects as addiction, art, friendship, loyalty, and sacrifice so beautifully and so completely that one could almost swear some indie studio had cooked up a script for it and sent in some handheld cameras to capture the magic. The key moment in the film, the sequence of events that makes it all work as well as it does, is the moment that Bertil sees a portrait of himself that Barbora painted for the very first time. As Bertil expresses shock, awe, and finally breaks down into tears at the sight of himself on the canvas, we can see behind his eyes the very pain he now knows he caused Barbora as a result of his actions in the earlier heist, and it is in this pain that the friendship finally begins to form and take shape. Barbora, rather than attempt to punish or humiliate Bertil, chooses to show him his humanity from nothing but her memory of him, and so moving is it to Bertil that he begins to open up to Barbora about all of the problems in his life, including his seemingly unshakeable drug addiction, which he credits for his loss of memory as to what happened to the paintings after the heist. And as he begins to open up to Barbora, Barbora likewise begins to open up to him about all the darkness she experiences in her mind, which she deals with through painting. But this film is not only about the beautiful (and often heartbreaking) friendship between Barbora and Bertil; it also acts as a treatise on the cost of artistic integrity. One of the great examples of this in the film comes during a couples therapy session in which Barbora and her boyfriend are the participants, and he declares that he feels it dangerous for her to continue on in this friendship, not because of Bertil’s past or addictive lifestyle, but because he sees Barbora using Bertil’s trauma as the basis for most of her darker works of art. The Painter and the Thief does this often: it forces one to ask questions about the cost of pursuing artistic integrity, and whether or not it is appropriate to use trauma as an art’s base, regardless of whether that trauma belongs to ourselves or to someone else who does not see a problem with the execution of that art. Is dark art an addiction to exploring trauma that we are unable to process, or is that trauma itself a rich field for artistic expression which both covers and exposes the most honest parts of our very human selves? In other words, do we have a responsibility to be vulnerable as artists, or are we simply mining traumas/uncomfortable issues for our own satisfaction/greater artistic visibility, and calling that vulnerability? This film does not seek to answer either question outright, but the way director Benjamin Lee allows moments to simply breathe in their spaces without rushing to get to the next point in the story of what he captures here is astounding. Documentary pacing is hard enough to do, but somehow Lee and company rarely (if ever) make a false step. Another instance of that exploration of artistic integrity comes when Bertil is released from his one year in prison that he serves as punishment for the art heist, as rendered in his sentencing by the Norwegian courts. As he attempts to contact Barbora, he is unable to reach her by phone, because she is not able to pay her phone bills. Being three months behind on her rent for her studio space, and entirely out of money without any exhibitions to show, her life is crumbling around her, and this demonstrates the high mental and emotional cost of not only committing one’s life to the creation and curation of art, but the damage one can do by stealing it. Eventually, the two reconnect after Bertil experiences a near-fatal car crash, waking up from a coma almost 6 months later, and he is put through physical therapy, and again we see Barbora unable to see anything but the humanity in this man who helped steal her two most valuable artworks. I’d love to say more, but even for a documentary, I could be venturing into spoiler territory there, so I’ll simply keep it at that. Truthfully, if you took me to task, and asked me to find a flaw within this film, I am not sure I would be able to with any sense of honesty or a clear conscience. The film does feel like it ends the tiniest bit abruptly (as if it leaves off the second half of what would have been a very special moment/conversation), but that truly is the only point of contention I have with this work. Not many documentarians have been able to do what Lee has managed to achieve here in capturing all the humanity between two people, and I sincerely doubt that many will be able to replicate or even come close to achieving this same level of earnestness in documentary filmmaking for many years to come. The Painter and the Thief is not just one of the first great documentaries of the 2020s, and not just one of the most excellent films of the year so far, but the most honest and quintessential picture of what it looks like, and what it costs, to choose to see the humanity in those that wrong us, and in the societal downcast. I’m giving “The Painter and the Thief” a 9.7/10 - The Friendly Film Fan

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorFilm critic in my free time. Film enthusiast in my down time. Categories

All

|